|

Jesus assigns each of us a unique mission of love within his universal mission of love. Our mission may not be what we would have chosen for ourselves if it were left entirely up to our own self-centered will, but it is the mission that will enable us to become the loving person God created us to be.

You can read this article at www.wordonfire.org/articles/leave-the-world-a-better-place-and-a-better-person/.

0 Comments

Escaping limitations imposed on us by the existence of objective truth appears as infinite freedom but turns out to be a "bad infinity."

This article can be read at www.wordonfire.org/articles/bad-infinity-good-infinity-and-the-truth/ "May we live long and die out”—this is the motto of the “Voluntary Human Extinction Movement” (VHEMT). This movement exhorts people to make a voluntary choice not to reproduce (or not to give birth to any more children, if they already have children), with the stated goal of bringing about the eventual extinction of the human race. Instead of “Be fruitful and multiply” this group’s message to the human race is “Be sterile and subtract.” But wouldn’t it be better to give future generations of human beings the chance to live and love, even if this earthly life sometimes also involves loss and suffering?

This article can be read at www.wordonfire.org/articles/be-sterile-and-subtract/ Action aimed at evangelization, social justice, etc. is a good thing, but action aimed at such goals that is also deeply rooted in prayer, in a profoundly contemplative life, is a much better thing. When we take time to “rest in God,” God’s Spirit, God’s dynamic power and love, can then flow more freely through our actions, making those actions more effective and impactful. The more our lives are rooted in the divine love, the more that divine love can flow through us and out into the world.

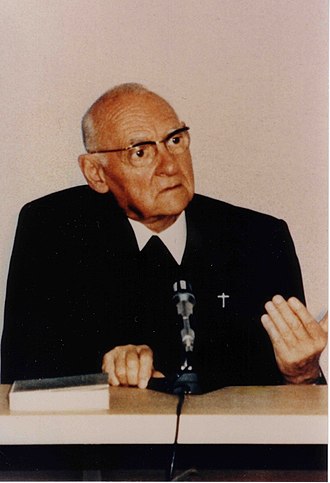

This article can be read at www.wordonfire.org/articles/systole-and-diastole-action-and-contemplation/?queryID=10f70ae2286fa1e5f36a56841406a61f Photo by Jacob Bentzinger on Unsplash Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) is considered by many to be the greatest theologian of the twentieth century. He is said to have been Saint John Paul II’s favorite theologian, and he was one of Pope Benedict XVI’s favorite theologians as well. People who are interested in learning about Balthasar's theology sometimes ask me where would be a good place to start, since Balthasar wrote over a hundred books. In this article, I recommend some possible starting points, including my personal favorite among all of Balthasar's works.

"Approaching Balthasar" can be read at www.catholicworldreport.com/2024/04/14/approaching-balthasar/ Love enables us to see the good more clearly: in other people, in ourselves, and in life itself.

This article can be read at blog.catholicwritersguild.com/2024/01/where-love-is-there-is-the-eye.html. "Where Love Is, There Is the Eye" is an excerpt from my latest book, The Book of Love: Brief Meditations (www.amazon.com/dp/B0BVSXX6P9/). Arguments in favor of abortion have undergone an evolution that parallels an evolution that took place in arguments favoring slavery.

This article can be read at www.wordonfire.org/articles/abortion-slavery-and-the-image-of-god/. Everyone needs at least one person in their lives who can honestly say to them, “How good that you exist!”

This article can be read at blog.catholicwritersguild.com/2023/12/how-good-that-you-exist.html "How Good That You Exist" is an excerpt from my latest book, The Book of Love: Brief Meditations (www.amazon.com/dp/B0BVSXX6P9/). Over a period of only three decades, abortion advocacy has evolved (or, better said, devolved) from treating abortion as a “necessary evil” (recall Bill Clinton’s self-proclaimed goal in the 1990s of protecting abortion “rights” while supposedly making abortions “safe, legal, and rare”), to promoting abortion as a positive good to be sought even in violation of the law (e.g., “Shout Your Abortion,” an organization whose website currently states: “Shout Your Abortion is normalizing abortion and elevating safe paths to access, regardless of legality”), to claiming that abortion is not only a positive good, but can also be sacred and holy ( “Holy Abortion”).

This article can be read at www.wordonfire.org/articles/calling-evil-sacred/. Like Jesus, we are called to “break ourselves open and pour ourselves out” in love for our fellow human beings, becoming “food” and “drink” for them as they make their way through their own journey to Love.

This article can be read at blog.catholicwritersguild.com/2023/11/food-for-the-journey.html. "Food for the Journey" is an excerpt from my latest book, The Book of Love: Brief Meditations (www.amazon.com/dp/B0BVSXX6P9/). Photo by Morgan Winston on Unsplash |

Rick Clements, Ph.D.

Rick writes and speaks about topics related to the Catholic faith, with a particular focus on the ways in which a rediscovery of beauty, goodness, and truth can help to revitalize our lives and our culture. Archives

May 2024

Categories

Header photo by Patrick Fore on Unsplash

© Richard Clements

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed